Why Did Megalodon Go Extinct? New Research Yields Surprising Results

Avocational paleontologist says the fossil evidence suggests that the world's largest shark may have eaten itself to death.

...the biggest whales were less likely to be attacked, thus they passed on their genes and future generations grew larger and larger. The shark actually caused whales to grow by feeding on them.”

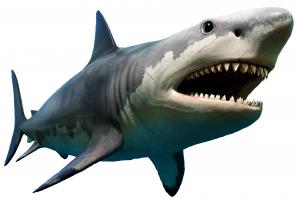

LOS ANGELES, CA, US, September 18, 2022 /EINPresswire.com/ -- Otodus megalodon was a gigantic mackerel shark that lived during the Miocene/Pliocene and hunted whales. It was one of history's largest marine predators, growing to 50 feet in length, with jaws that could engulf a couch. It's also (luckily) extinct. Researchers and shark enthusiasts have long wondered why. Whales are still here, so what happened to the shark that preyed on them? — Max Hawthorne

A possible answer to this question has been provided by award-winning author and avocational paleontologist Max Hawthorne. Best known for his popular Kronos Rising series of sci-fi thrillers, the “Prince of Paleo-fiction” does paleontological research on the side, with credits including solving the mysteries of how plesiosaurs swam and why they had such long necks (the latter he solved using snake neck turtles). Hawthorne is also a bit of a Megalodon junkie. Several years ago, he “made waves” with his radical Megalodon Scavenger Theory, which suggested that, as the extinct shark became bulkier and less maneuverable as an adult, it shifted from being a primary predator and opportunistic scavenger to a primary scavenger and opportunistic predator. Most recently, he demonstrated via fossils he collected that Megalodon moms were larger than previously thought, and may have approached 60 feet in length.

“Megalodon’s extinction is a hot topic,” Hawthorne said. “Many theories have been put out. One more enthusiastic one was that energy from a supernova killed off the shark. I guess the notion that it took a cosmic explosion to kill off an otherwise indestructible ‘monster’ was appealing. We know now, however, that said explosion took place around 2.6mya, whereas the shark died off around 3.6 million years ago.”

Hawthorne believes that Megalodon died off because of its diet, but not in the traditional sense. Rather, it was a triple whammy - a combination of the shark’s excessive size, overspecialization, and its reliance on a food pyramid that in the end came crashing down. “It may rankle some, but fossil evidence in the form of Megalodon’s tooth morphology, as well as fragments of fossilized whale bone, supports my theory that the adult sharks got most of their food from rotting whale carcasses. They were too slow to hunt cetaceans that swam three times as fast and were far nimbler.”

He went on to add that being a primary scavenger wasn’t a bad thing. “Megalodon’s hunting strategies were advantageous for millions of years. Think of it as an inverted triangle. At the top of that triangle were the younger sharks, say, 15-25 feet long. They were the active hunters, quick enough to catch and kill the baleen and toothed whales of their day, which were around their size. They were far more numerous than the giant adults, which were at the bottom. Think of great whites. We know of thousands of fish that are 10-12 feet long, and hundreds that are up to 16 feet. But how many are there over 20? Very few. Same thing applied to the “Meg”. So, you had all these younger sharks making kills. And what was left after they fed? Carcasses. The younger fish were basically providing food for the older ones. Lots. And the adults developed anterior maxillary teeth designed to fracture rib cages on carcasses (which were often stripped when they got there), so they could access the nutritious heart and lungs.”

Asked how this had any bearing on Megalodon’s extinction, Hawthorne elucidated. “About a million years before the Meg died off, whales started getting bigger. I believe this was a result of evolutionary pressure – the biggest whales were less likely to be attacked, thus they passed on their genes and future generations grew larger and larger. This is supported in a paper by Lambert et al. The shark actually caused whales to grow by feeding on them. This gradual increase in whale size became problematic for the younger Megalodons, as a 20-foot predator cannot attack a 40-foot leviathan. Not without risk of being injured or killed. It was also a problem for the adult Megalodons, which were physically capable of killing whales that size, but were too slow to catch them. So, the shark was faced with larger and larger whales traveling in pods which were not on the menu. That was the first whammy, or strike one, if you will.”

According to Hawthorne, the second “whammy” was also whale-related. “At the end of the Miocene and during the Early Pliocene, many of the smaller species of whales that were Megalodon’s bread and butter began to die off. For example, Diunatans, a 25-foot (8 meter) baleen whale, and Bohaskaia, a 20-foot (6 meter) beluga-like toothed whale, both went extinct at the close of the Zanclean (Early Pliocene). That’s around 3.6mya, and coincidentally around the same time Megalodon vanished. No smallish whales meant no prey for the sub-adult sharks. It also meant no carcasses for the huge adult sharks – the species’ all-important brood stock. Think about it. Around 3.6mya many small whales have died off. Giant baleen whales remain, but the mega shark is gone. I find that interesting, don’t you?”

The third, and final nail in Megalodon’s coffin is something that affected the most vulnerable of the sharks – their babies. “One thing I don’t think anyone’s ever focused on is an extinct species of sirenian called Nanosiren garciae. Nanosiren was a dwarf dugong that inhabited the warm, shallow waters of South America and the United States. It was small - only 2 meters long and ~150kg - making it the perfect prey item for neonate Megalodons. The baby sharks would have feasted on blubber-rich, high-caloric meals which helped them grow. Coincidentally, Nanosiren also died off around 3.6 million years ago. Reliance on it for food,” Hawthorne emphasized, “was most likely strike three for Megalodon. No food for the babies = no adults. The species simply couldn’t withstand this triple whammy. Their food pyramid collapsed under its own weight and their population went with it. And then, just like that, the world’s largest carnivorous fish was gone.

Kevin Sasaki

Media Representative

+1 310-650-3533

email us here

Visit us on social media:

Facebook

Twitter

Other

Legal Disclaimer:

EIN Presswire provides this news content "as is" without warranty of any kind. We do not accept any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images, videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright issues related to this article, kindly contact the author above.