The CEO Scorecard: How Directors Select a CEO When They Have Real Skin in the Game

We recently published a paper on SSRN (“The CEO Scorecard: How Directors Select a CEO When They Have Real Skin in the Game”) that examines how boards can improve succession planning through use of an outcomes-based CEO scorecard that matches candidates’ skills against the value drivers of the business.

Shareholders, stakeholders, and corporate insiders place considerable emphasis on the importance of reliable CEO succession planning. Survey data show that public company directors recognize succession planning as one of their most important responsibilities. Companies aim to boost shareholder confidence in their succession plans through voluntary disclosure. Today, nearly all large public companies disclose at least some information about their planning processes in the annual proxy. In addition, a large industry of recruiters and advisors exists to support companies with the planning, grooming, and hiring of CEO talent.

Succession planning within firms is often opaque, but research has pieced together suggestive evidence that sound succession planning can yield significant benefits. Cvijanović, Gantchev, and Li (2023) find that companies that follow a pre-established succession plan are more likely to exhibit positive economic outcomes, including greater willingness to terminate an underperforming CEO, lower uncertainty (stock price volatility) during and up to one year after the transition, and longer tenure for the replacement CEO.

Despite agreement on its importance, it is far from clear that CEO succession planning is any better today than a decade or two ago. Major companies have experienced succession turmoil in recent years, including Boeing, Disney, General Electric, and Starbucks. Why is this?

Research sheds some light on the problem. Cziraki and Jenter (2022) find that companies have trouble matching (what they believe to be) firm-specific CEO talent needs with the observable skills of external talent. Instead, boards prefer to recruit from known candidates—internal executives and external candidates already known to at least one director. The authors argue this shrinks the available talent pool and is reflective of an inefficient CEO labor market. Jenter, Matveyev, and Roth (2023) study succession events involving the sudden death of the incumbent CEO. They find companies have surprising trouble naming a replacement without major effects on stock price. They observe that “the matching process [is] far from frictionless, and the resulting match quality highly heterogenous”—meaning the quality of replacement CEOs varies considerably.

Part of the problem appears to stem from biases of judgement. Kaplan and Sorensen (2021) find that companies are more likely to select CEOs with greater interpersonal skills, but these CEOs do not necessarily exhibit superior performance. The authors conclude that “boards overweight interpersonal skills in their CEO hiring decision.” Excessive influence by the outgoing CEO might also contribute to the problem. A survey of Chief Human Resource Officers conducted by researchers at University of South Carolina Business School finds that incumbent CEOs have greater influence than their own boards in naming a successor.

Still, because researchers cannot directly observe board succession processes, we do not have clear insight into what actually happens in boardrooms as companies plan for and deliberate over CEO candidates. For this reason, direct institutional knowledge is highly valuable in shedding light not only on research findings but delineating why and where many companies are deficient, and how they might improve.

In this Closer Look, we consider the perspective of ValueAct Capital, an institutional investor with extensive, direct experience serving on the boards of directors of portfolio companies during multiple succession events. Through an analysis of these events, ValueAct has identified common deficiencies, including the manner in which required skills are identified and framed and the process by which they are evaluated.

ValueAct’s Experience with CEO Succession

ValueAct is a governance-oriented investment firm with approximately $10 billion under management. It has a track record of engaging cooperatively with portfolio companies through shared analysis, advice (often under NDA), and by serving on the board of directors.

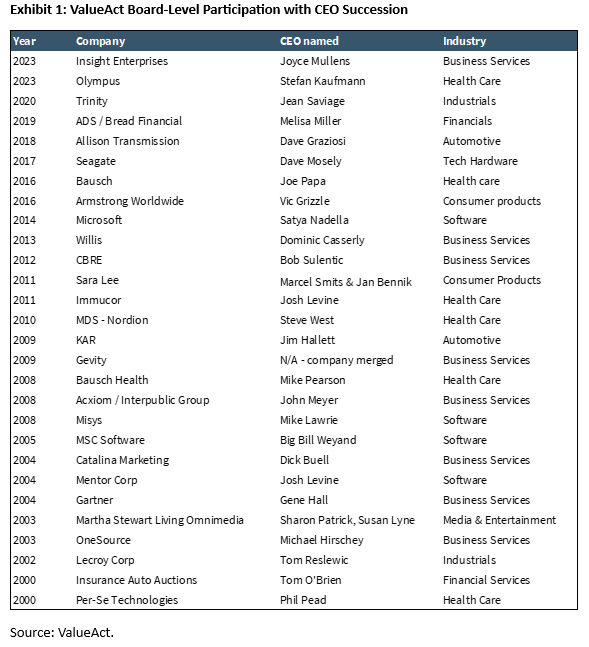

Since 2000, ValueAct has served on the boards of 47 portfolio companies, including those of Microsoft, Salesforce, Adobe, Olympus, and JSR. Among these, ValueAct representatives have participated in 28 CEO succession events to date (see Exhibit 1).

Through board representation, ValueAct has gained important insight into how companies handle succession.

First, ValueAct has observed that succession processes are rarely smooth, but instead are often stressful, emotional, and taxing on personal relationships. This is due in part to the fact that a surprisingly high percentage of CEO succession events are not orderly. Many are done when the business is struggling, the management team dysfunctional, or the company faces a significant external crisis. ValueAct characterizes 17 (61 percent) of the 28 succession events it has participated in as disorderly and only 11 (39 percent) as orderly.

Even orderly successions can be riddled with interpersonal disruption, such as directors developing attachment to a particular candidate or type of candidate too early in the process, CEOs advocating for a preferred candidate who might not fit the future needs of the company, or members of the boardroom communicating to a candidate that they are the preferred successor when a decision has not yet been made. Behaviors such as these inevitably lead to conflict and disrupt objective decision making.

ValueAct has also observed that many companies do not use rigorous scorecards built on quantitative metrics to guide the CEO evaluation process. Instead, the qualifications for a replacement CEO are often expressed as a list of vague qualities or adjectives, such as “leadership,” “vision,” “customer-centricity,” “communication skills,” “operational excellence,” and others. It is impossible for directors to utilize a scorecard structured in this way to make an objective evaluation of candidates when the qualities being assessed are themselves subjective and lead to differing opinions.

Why are scorecards not more rigorous? Part of the problem lies with the board. All too often, board members lack a clear consensus around a company’s strategy and priorities and struggle to define the company’s future success in terms of specific outcomes. Without consensus, it is not possible to develop a rigorous and objective scorecard by which to evaluate potential internal and external candidates.

Executive recruiters also are not in a position to provide this direction. These firms provide valuable support during a succession event—including process management, a broad network of candidates, experienced partners, software tools, and psychological assessments—but they are not strategy consultants and are not expected to guide the board on issues of the company’s industry, strategy, or key performance drivers. Without specific direction from the board, it is difficult to expect an outside search firm to develop a CEO scorecard that reflects the specific capabilities and qualities necessary to address the company’s near and long-term strategic needs.

ValueAct’s experience has led to two key insights.

One, a good CEO succession process should lower the emotional stakes, minimize personal biases, and stimulate fact-based discussions. The more grounded in facts and data, the more respectful and productive the debate.

Two, a good CEO succession process requires the board to first form consensus around a company’s strategies and priorities. From this consensus, candidates should be evaluated based on their demonstrated ability to achieve specific performance objectives rather than the degree to which they exhibit subjective managerial qualities.

“Adjective-Based” Scorecards

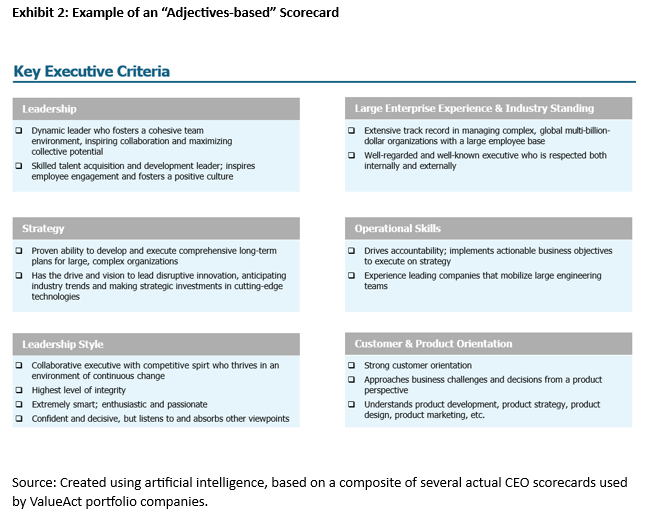

Companies commonly use skills and competencies or an “adjective-based” scorecard to define the criteria for a successful candidate, guide the interview process, and standardize the evaluation of candidates.

A typical CEO scorecard might include the following key criteria, with definitions to support each:

- Leadership

- Large enterprise experience

- Strategy

- Operational skills

- Leadership style

Customer and product orientation

(See Exhibit 2.)

A successful candidate presumably is one who demonstrates these capabilities and qualities. However, this scorecard does not require candidates to demonstrate specific business achievements, and does not explicitly tie any of these attributes to the needs of the company. It requires no quantification of results and asks for no numbers, no financials, no rankings, no events, and no specific accomplishments. A scorecard such as this allows the boardroom discussion to devolve into a series of subjective arguments, with some board members arguing in favor of one candidate’s “leadership ability” or “operating skill” and others arguing in favor of another’s.

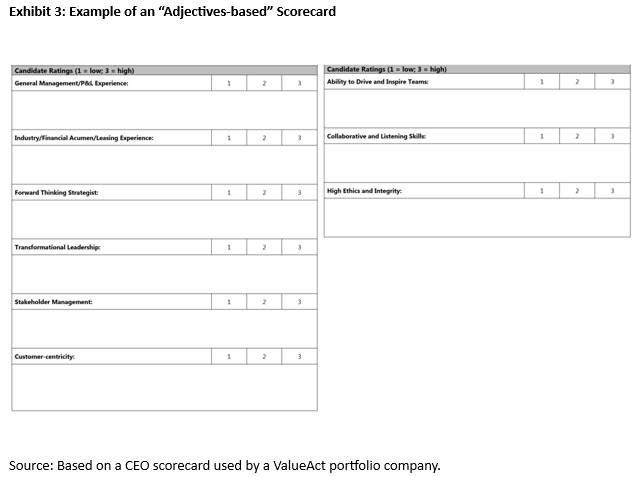

Another example of an adjectives-based scorecard asks the board to rank candidates on a scale of 1 to 3 (with 1 being “low” and 3 being “high”) according to the following criteria:

- General management/P&L experience

- Industry/financial acumen

- Forward thinking strategist

- Transformational leadership

- Stakeholder management

- Customer-centricity

- Ability to drive and inspire teams

- Collaborative and listening skills

- High ethics and integrity

(See Exhibit 3.)

This scorecard is based on one used by a company wrestling with major strategic and capital structure questions. Yet nowhere in the scorecard were these issues specifically addressed. It is unclear how ranking candidates on a scale of 1 to 3 according to these attributes would lead to reliable insight into how a candidate would address the strategic and financial issues the company very urgently needed to address.

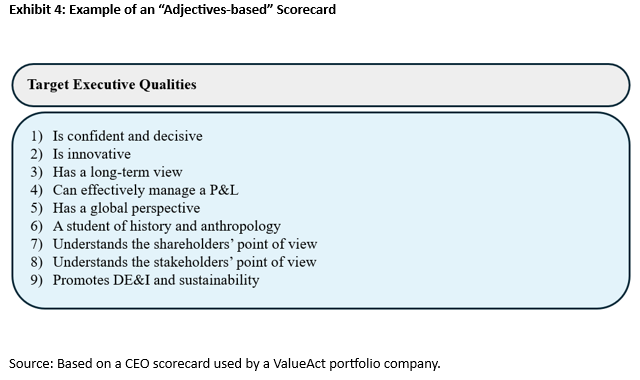

A third example of a CEO scorecard asks a series of presumably yes/no questions:

- Is confident and decisive

- Is innovative

- Has a long-term view

- Can effectively manage a P&L

- Has a global perspective

- A student of history and anthropology

- Understands the shareholder’s point of view

- Understands the stakeholder’s point of view

- Promotes DE&I and sustainability

(See Exhibit 4.)

Scorecards such as these do not map to any specific past or future outcomes. As such, they do not really help to focus the board’s assessment of the candidate’s career history. Adjectives can be checked in reference calls against subjective judgments and memories but cannot be objectively measured or compared directly across candidates. What evidence should a board look for to assess the “global perspective” of a candidate? How can it measure a “confident and decisive” personality?

Finally, these types of scorecards do not directly map to any business plan or ideas a CEO candidate might present to the board, nor do they provide evidence that the candidate is capable of achieving what they propose. The language of adjectives is completely different from the language of outcomes. A reliable succession process requires both.

Outcomes-Based Scorecard

ValueAct believes that a CEO scorecard should be outcomes-based and facilitate the objective evaluation of a candidate’s demonstrated skills and abilities. To do so, it should include financial and nonfinancial KPIs that map to the forward-looking strategy and goals of the company. When properly structured, the process allows for skills to be measured and tested through data and actual evidence of managerial skill.

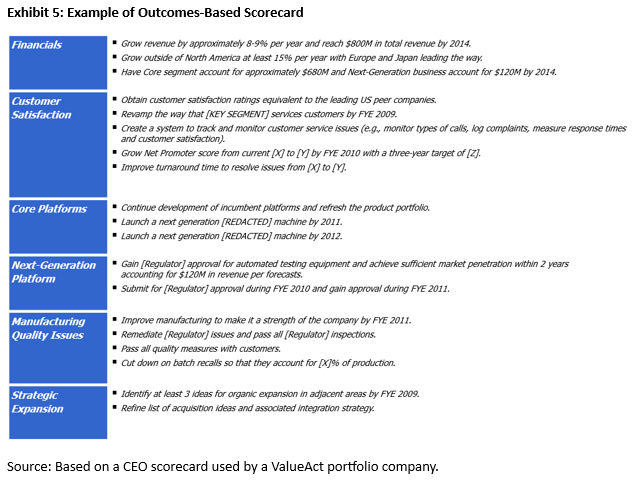

In one scenario, a ValueAct portfolio company was suffering from poor customer relations, manufacturing quality issues, and government accusations of price gouging, while its core business faced the threat of disruptive technology. The board was under pressure to act with urgency. A faction of directors wanted to quickly promote an internal successor. Some directors had even signaled to that executive that such a decision was forthcoming.

To another faction, this decision felt rushed. Lacking an alternative, this group of directors backed the sitting CEO. The gridlock and conflict persisted for some time, until the board took the time to build a CEO scorecard along the lines recommended by ValueAct. It included the following objectives:

- Grow revenue by 8-9 percent to reach $800 million by FY2014

- Obtain customer-satisfaction ratings equivalent to leading U.S. peer companies

- Launch next-generation product by FY2011

- Improve manufacturing to make it a strength of the company by FY2011

- Identify at least 3 ideas for organic expansion by FY2011

(See Exhibit 5.)

The specificity and clarity of the scorecard defused the emotions in the boardroom. Directors were able to assess candidates against each KPI using facts and data. In a surprising twist, neither faction “won.” The board collectively decided on an outside CEO who was effective in meeting these goals. The company later sold to private equity for a premium

Testing Candidates Against An Outcomes-Based Scorecard

Once a scorecard is established, the board can map each candidate’s track record (through indepth research) to the desired outcomes.

The track record of candidates with outside public-company experience can be evaluated through public data, including:

- Total shareholder return versus peers

- Revenue growth, earnings growth, business outcomes

- Results by business unit or geography

- Media coverage, research analyst reports

Private-company CEOs or divisional leaders with P&L responsibility can be asked to provide similar data (with the exception of total shareholder returns). Functional leaders without P&L responsibility require a more nuanced assessment where case-specific KPIs can be tracked down. Examples might include:

- Subscriber trends versus peers

- Net promotor scores

- Market share data

- Function-specific metrics (such as return on advertising spend for CMOs, etc.)

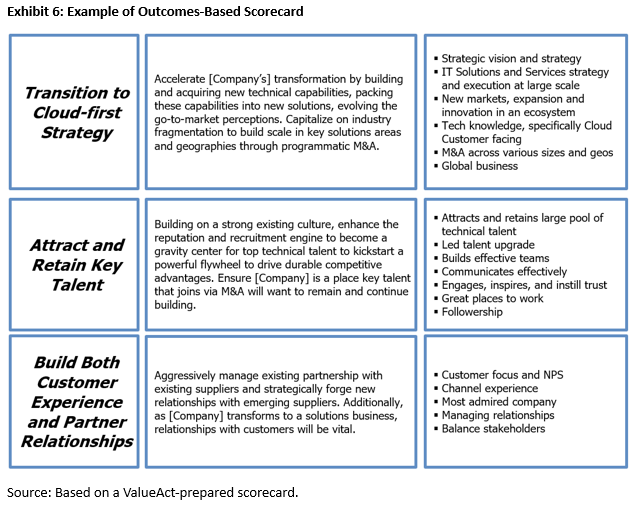

In another situation, a ValueAct company was undergoing a CEO succession during a time of strategic transformation from legacy technology to cloud-based services. This transformation required new technical talent, new billing and pricing practices, new go-to-market operations, and a new M&A strategy. The CEO scorecard was distilled to three main objectives, each supported by specific KPIs:

- Transition to cloud-first strategy

- Attract and retain key talent

- Build both customer experience and partner relationships

(See Exhibit 6.)

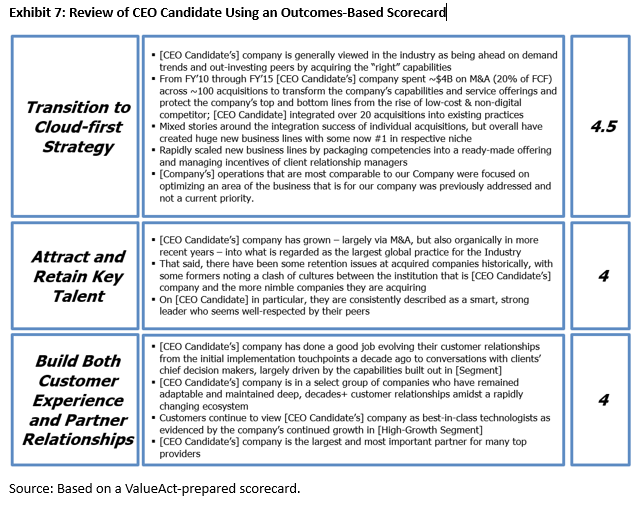

The ValueAct investment team supported the board of directors in the evaluation of internal and external candidates through this scorecard. An assessment of one of the external candidates is reproduced in Exhibit 7, with certain information modified.

The candidate evaluation form includes the specific operating and financial performance of the candidate relative to each objective on the scorecard. It includes M&A deal statistics, voice-of-customer research via industry trade reports and firsthand interviews, and employee perception based on interviews. It demonstrates the candidate’s potential fit with the company’s objectives and includes items to watch out for and explore through interviews.

The company ultimately selected a leader aligned with its objectives who produced successful results, with total shareholder return among the best in the sector and execution on the company’s transformation plan.

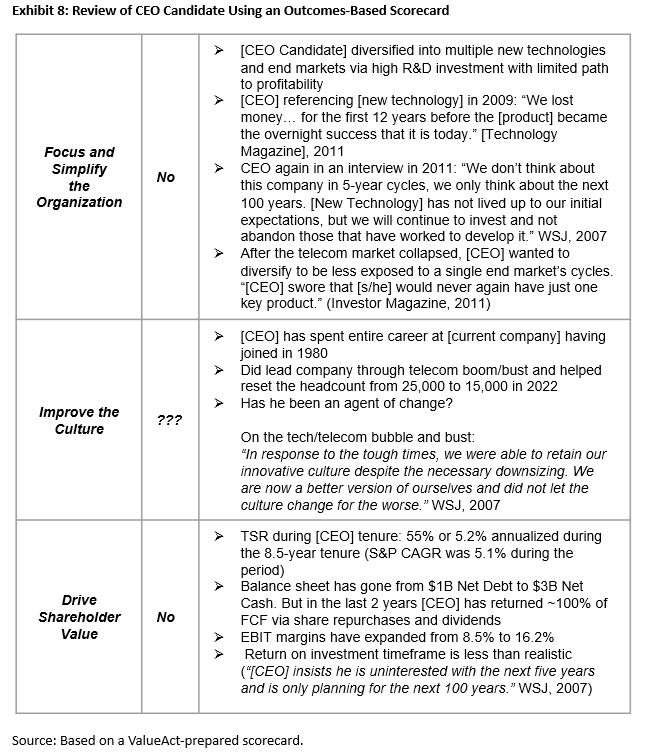

A different ValueAct portfolio company competed in several loosely connected industries, each of which faced disruption from startups. Despite having more resources than competitors, the company was unfocused in its investments, distracted by intra-company politics, and had lost investor confidence.

The executive search firm presented one candidate with a compelling life story full of dramatic anecdotes about technical breakthroughs. In one inspiring story, he had personally written a product’s chemical formula on a whiteboard, solving a problem that had frustrated the company’s scientists. To the board, he seemed a perfect choice.

A comparison of his performance to the CEO scorecard, however, led to a different conclusion. The CEO scorecard contained the following main objectives:

- Simplify the company’s complex and incoherent strategy

- Fix its dysfunctional culture

- Deliver shareholder returns

The ValueAct investment team assisted the board in mapping the candidate’s performance against these objectives, using publicly available information from financial statements, quarterly conference call transcripts, and a reconstruction of its M&A track record (see Exhibit 8). The results revealed that the CEO had a track record of complicating and expanding a company’s scope, not simplifying it. It was unclear that he had ever changed a culture. And shareholder returns at his company were subpar. The board decided not to pursue the candidate.

This same evaluation process was applied to numerous other high profile CEO candidates that had were on the board’s shortlist. The board was forced to expand its scope beyond its shortlist. Eventually, a relatively unknown internal candidate emerged who strongly matched the scorecard criteria. In a move that surprised many analysts and investors, he was chosen as CEO, then delivered on all scorecard objectives. Returns for shareholders were tremendous.

Stock Price Performance

It is easy to develop a new or revised approach to succession planning. The question is whether use of an outcomes-based scorecard improves the CEO selection process.

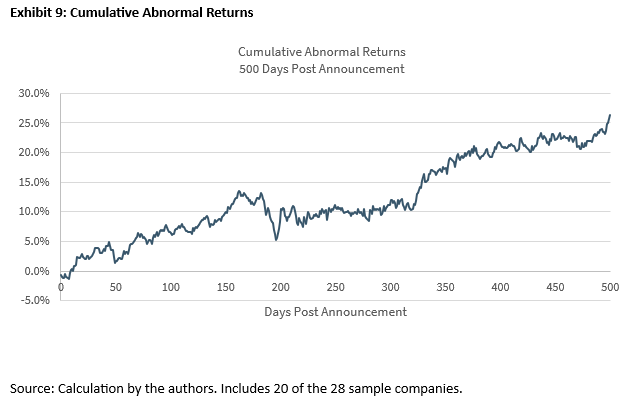

It is very tricky to develop a reasonable measure for the success or failure of the CEO selection process. One common approach is to use the stock-price performance of a company after the new CEO is announced. Using this approach, the CEOs in our sample of ValueAct CEO successions (see Exhibit 1) exhibited positive cumulative abnormal stock-price returns, outperforming the market on average by roughly 25 percent over the 500-day (approximately two-year) period following their appointment (see Exhibit 9).

While these results are impressive, it is important to note that our sample consists of situations where ValueAct saw value in changing the company strategy in addition to the change in CEO, which makes the succession events less typical. It is difficult to benchmark actual returns to the counterfactual of what would have happened if a change in strategy had not been implemented in parallel with the change in CEO. On the other hand, these results might also be underestimated to the extent the market believes an investment by ValueAct improves the selection process of a new CEO, in which case this value would be priced in when the initial investment is disclosed—and before the replacement CEO is announced.

In either case, the average returns in our sample are impressively positive and suggest there is value to using an outcomes-based scorecard approach.

Conclusion

In summary, ValueAct believes the CEO succession process can improve if it is framed in terms of the value drivers of the business and each candidate’s demonstrated capability to achieve those value drivers.

- The board should develop a clear scorecard of desired outcomes that will define the company’s success in the future, including the managerial qualities or adjectives required of that individual.

- The CEO candidates should each present a vision for the company, with a specific business plan.

- The CEO candidates and their plans should be “scored” using facts and evidence from their career achievements vs. the board’s desired outcomes.

This “scoring” must go beyond reference calls and involve deep due diligence into the candidates’ prior roles, including the financial and non-financial performance of the businesses they have led.

In many ways, a properly structured succession process will resemble the research an investment firm does before purchasing a security. The scorecard itself is analagous to an investment thesis, involving a thorough study of the industry, business performance drivers, and the pathway to shareholder value creation. The candidate assessment will resemble a management assessment process, using personal interviews, a “say versus do” analysis of public commitments, and 360-degree reviews from current and former colleagues to gauge managerial capability.

In sticking to this investment mindset approach, the board will reduce (but not eliminate) the risk associated with the selection of a new CEO by understanding specifically how he or she is expected to perform relative to the company’s business situation and forward-looking plan.

Why This Matters

- Shareholders and stakeholders have put considerable emphasis on companies having a sensible and rigorous CEO succession plan in place, and yet experience shows time and again that many boards fail to name a successor in a timely manner and, even when they ultimately do so, fail to select an individual who is highly likely to succeed. What is the cause of this failure? Are boards unable to identify the managerial attributes needed to succeed at their company, or can they identify these attributes but fail to measure whether a candidate actually has them? What does this say about the general efficiency of the labor market for CEO talent?

- Through its experience serving on the board of directors of portfolio companies, ValueAct has observed that CEO succession processes are often disorderly, emotionally charged, and overly focused on vague managerial qualities (adjectives) rather than specific performance objectives. How valid is this observation? If valid, what are the main causes of these deficiencies?

- In ValueAct’s experience, a key shortcoming in CEO succession is that boards struggle to identify and agree on the key strategic and operational goals for the company. This lack of clarity makes outcomes-based CEO scorecarding difficult. Why is this the case? Is it because most board members come from outside the industry? Is it due to deficiencies in board book KPIs that have failed to illuminate key issues to the board? Is it a process issue in that boards are not focused enough on routinely debating and refining these issues? Or, is it the case that many directors have limited experience in selecting the CEO and/or are not especially good at selecting a CEO?

- The objectives-based CEO scorecard and candidate assessment forms discussed in this Closer Look require the board to identify and review quantitative information about each candidate’s performance relative to company objectives. How difficult is it to accurately find this information? When accurately captured, does this information provide a more reliable guide to (prediction of) whether a given candidate will succeed or fail? If so, why don’t more boards and executive recruiters already require this information?

- ValueAct concludes that a successful CEO evaluation process resembles the research process before an initial investment. Is this claim valid? If so, would boards benefit from adopting an “investment thesis” mind frame? Would CEO selection processes improve (i.e., fail less often) if companies included directors with investment experience?

Link to SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5046840

Legal Disclaimer:

EIN Presswire provides this news content "as is" without warranty of any kind. We do not accept any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images, videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright issues related to this article, kindly contact the author above.