The Legendary Alpine Drive Estate

Contrary to popular legend, the Harry and Virginia Robinson residence completed in 1911 on Elden Way was not the first mansion built in Beverly Hills.

That honor goes to the Llewelyn Arthur (L. A.) Nares “bungalow” constructed in 1907 at the northernmost end of Alpine Drive overlooking then-uninhabited and starkly beautiful Coldwater Canyon and fields (not city) to the south. Not only was this the first Beverly Hills mansion ever built, it was also the first teardown, and the scene of one scandal and tragedy after another as the property passed from owner to owner before World War II.

The pioneering property owner, L. A. Nares, was born (in 1860) and educated in England. A man of ambition and vision, Nares became a banker in England and Canada, and then a surveyor in Canada and the western United States, before becoming a highly successful real estate investor who developed a series of very profitable irrigation canals in California.

Aerial photograph from 1920. Photo Credit: Bison Archives.

In 1896, he and several partners had purchased the 100,000-acre Laguna de Tache Spanish land grant outside Fresno. The ranch had some of the best farmland in the state, but it required a steady supply of water in the rainless summer and fall months.

With the land grant, Nares made substantial claims on the flow of Kings River. Soon, Nares was president of the Fresno Canal and Irrigation Company, which eventually served an area of 400,000 acres, as well as the Consolidated Canal Company and the Summit Lake Investment Company. The town of Lanare, California, was named after him. Lanare, of course, being a modified version of L. A. Nares.

During this period, he married Anna L. England, an Englishwoman with whom he had two sons, before settling permanently in California. Recognizing that Los Angeles was becoming the business capital of Southern California, Nares and one of his partners, William Ewart Gladstone Saunders, opened a real estate office on South Broadway called Nares & Saunders.

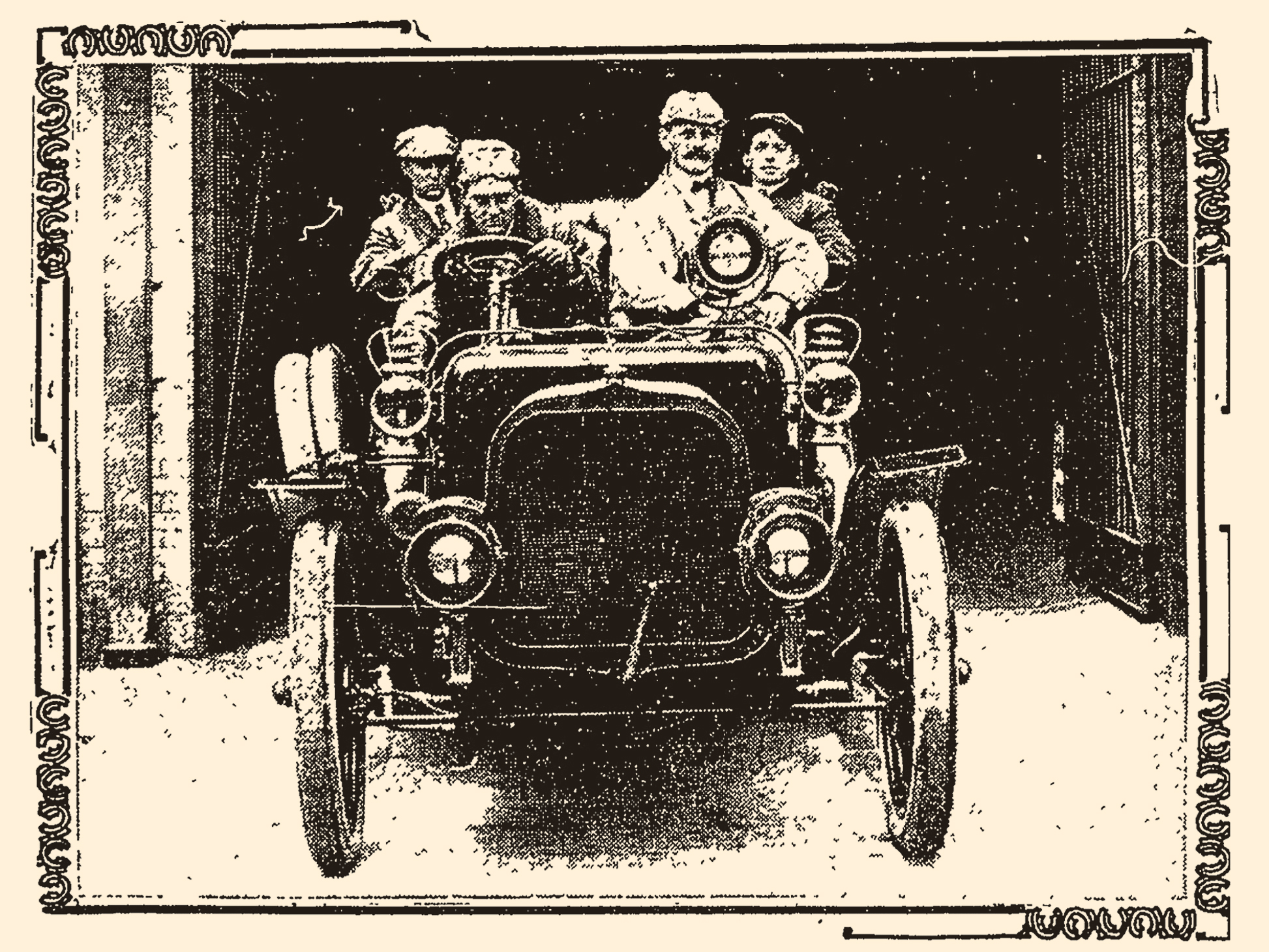

A. Nares fit the image of an English gentleman-adventurer. He was tall and thin, with a perfectly trimmed handlebar mustache and steely, if not downright intimidating, eyes. Having succeeded at virtually every business venture that he launched, Nares was determined to make history in 1905. An avid enthusiast of that new-fangled contraption the automobile, he vowed to complete the 503-mile drive from Los Angeles to San Francisco in just twenty-four hours, breaking the previous record by at least five hours.

Nares purchased a big Pope-Toledo automobile, one of the most powerful cars on the road—30 horsepower!—which was capable of reaching up to sixty miles an hour, or a mile a minute on a straight track. On the often-treacherous and potholed dirt roads between Los Angeles and San Francisco, however, the car would be lucky to average twenty miles an hour. Accompanying Nares was a crew of three: two drivers and a first-class mechanic, an absolute necessity for a long-distance race.

At 4:00 a.m. on the morning of July 16, 1905, Nares and his crew left the Western Motor Car Company’s garage on Hill Street in Los Angeles “with a noise like a monster rocket seeking flight . . . and shot up Broadway.” Nares and his crew reached Santa Barbara at 8:59 a.m., having been delayed only briefly by a tire puncture. They reached distant Paso Robles at 6:00 p.m., and Soledad at 11:30 p.m.

Rendering of L.A. Nares residence. Photo Credit: Los Angeles Times.

Then, they turned toward the peninsula and San Francisco. During their determined race north, Nares and Company had to stop to change the car’s oil. They had been delayed for two hours by a broken spring. And a fire had even broken out in the passenger compartment. But by dawn on July 17, they finally saw the lights of San Francisco. In a “cannonball finish,” they sped up Market Street. The time on the Ferry Building tower’s clock? 4:50 a.m. Although this was fifty minutes past his twenty-four-hour goal, Nares had nevertheless done as he’d promised: he had smashed the previous record.

His next challenge was the construction of a grand country home at the top of Alpine Drive. This was an act of incredible daring, because Nares’s new estate was literally built in the middle of nowhere. Los Angeles had not grown much beyond Western Avenue, and Beverly Hills had just opened on September 22, 1906. Only four unpaved north-to-south streets—Rodeo, Beverly, Canon, and Crescent Drives—had been graded through the bean fields in the flats.

Alpine Drive was just a line on a map. The street did not exist. Nares had to cut a dirt road from the flats up to the site of his new home, and then he had to bring in electricity, a telephone line, and water.

Nares named the new street Knaresborough, after himself. After all, he had paid for the road. The name was changed to Alpine Drive by the City of Beverly Hills in 1917.

Nares selected Myron Hunt and Elmer Grey, Southern California’s premier architects at the time. They had designed many mansions in Pasadena and Los Angeles and later were architects of the Beverly Hills Hotel (1912). Nothing but the best for Nares.

Hunt and Grey had “studied the landscape in designing the house and have made it fit into the lines and curves of the hills on which it is to be built,” reported news accounts. The house was “a long, low, rambling structure, curving with the hilltop, one story high from the front, but overhanging a steep hill, and presenting a two-story façade from the rear.” The framed façade was plastered. The roof had green shingles. Redwood was used throughout the interior.

“A feature of the house is the great hall in the center of the building, 20 x 40 feet and two stories high, built in old English style of architecture with an enormous fireplace on one side and large bay windows at front and rear. To the right of the great hall are the dining-room, kitchen, den, and sewing-room, connections with which are gained by using the glazed veranda. To the left are four bedrooms with baths en suite. . . . The basement will contain the quarters for the servants, a billiards room, and a garage.” Nares, of course, needed a large garage. The mansion’s cost was $17,000.

Life in the Nares mansion, however, proved far from happy. In 1908, just a year after the estate’s completion, Anna Nares filed for divorce, charging adultery. This was a shocking action for any well-bred woman to take at the turn of the century. But having returned from a trip to Canada, she found her husband deep in the throes of an affair with another woman.

Far from contesting the divorce, Nares voluntarily settled most of his fortune on Anna, including a $17,500 lump payment, $7,500 a year alimony, and $250,000 worth of property in Canada and in Kings County, California. Anna took their sons and returned to Canada.

The Alpine Drive Estate. Photo Credit: Bison Archives.

In 1909, Nares married Kathryn Evans, who was twenty years his junior. Two years later, Nares—perhaps at the urging his new wife, who was tired of being surrounded by coyotes rather than people—sold his four-year-old hilltop estate to fellow auto enthusiast Thomas Thorkildsen. Thorkildsen felt that the 6,400-square-foot Nares mansion was too small for his ambitions, and he completely rebuilt the property, creating the largest mansion and finest estate in all of young Beverly Hills.

Thomas Thorkildsen was born in Wisconsin in 1869. By 1908, he was the country’s rough-and-ready “Borax King,” a multimillionaire who was a spendthrift, a big-game hunter, automotive enthusiast, owner of an impressive yacht, and—much to the horror of a socially conservative turn-of-the-century society—a well-known nudist.

At age twenty, Thorkildsen began his career at Pacific Coast Borax, which would become U.S. Borax, the “twenty-mule-team” company. In 1898, he invested $17,000 of his own money in a borax mine in Ventura County, partnered with his boss, Stephen Mather in the Thorkildsen-Mather Company, and launched the Sterling Borax brand. In 1905, Thorkildsen bought a new borax strike in the Santa Clarita Valley’s Tick Canyon for $80,000. The mine made him a millionaire.

By 1908, after further acquisitions, Thorkildsen had officially become known as the “Borax King of America” in the media. He spent his money lavishly, as if it would never run out. He married Selida Eudora Garinger, known as Dora, a divorcée of Blackfoot Indian descent, and looked for new ways to spend his money. The Nares estate caught his eye. In 1911, he purchased the estate for $40,000, and then bought several smaller adjacent properties to enlarge it.

To the amazement of local residents, the Borax King wanted a hilltop palace that would dwarf—and look down upon—the houses in the Beverly Hills flats and the mansions being erected on Lexington Road by the Beverly Hills Hotel. Surprisingly, he chose a relative unknown, Thomas Franklin Power, to design the mansion and the grounds. Power created an Elizabethan-style mansion with formal English gardens.

Completed in 1913, the $200,000, two-story, 12,000-square-foot mansion was the largest house in Beverly Hills well into the 1920s. The twenty-six-room mansion stretched 191 feet across the hilltop knoll. The façade of the first floor was plastered brick. The second floor was plaster and half-timbers, which looked like intricately designed lace from a distance.

In 1905, L.A. Nares driving from San Francisco to Los Angeles. Photo Credit: Los Angeles Times.

To the further amazement of residents, the grand—and just five years old—Nares mansion was demolished. Thorkildsen had transformed Beverly Hills’ first grand mansion into its first teardown.

Inside the new Thorkildsen mansion were twenty-six rooms, six bathrooms, and seven fireplaces. All of the main rooms on the first floor opened onto brick-paved terraces and patios. An intercom system connected every room, as well as different buildings on the grounds.

Lavish was an inadequate term to describe the interior of the mansion. The 34-foot-wide reception hall was paneled in mahogany. At each end of the 46-foot-wide living room were wide bay windows. The centerpiece of the living room was a massive floor-to-ceiling, Gothic-style fireplace. Off the living room was a redwood-paneled smoking room. Oak-paneled hallways led to the ivory-enamel dining room, which opened through French windows onto a sitting porch and terraces. The western side of the first floor also had several guest rooms. The 41-by-20-foot salon at the western end of the house had large bay windows and opened from French windows onto a paved, 29-by-16-foot terrace. A sweeping stone staircase led from this terrace to the gardens. To catch the morning sun, the kitchen was located on the eastern end of the ground floor.

A winding staircase to the second floor was lit by two-story-tall leaded glass windows. On the second floor were the master and mistress bedroom suites. Thorkildsen’s suite had a bedroom, sleeping porch (for hot summer nights, before air conditioning), dressing room, and bathroom. Dora’s larger suite had a bedroom, sitting porch, sleeping porch, dressing room, and bathroom. Also on the second floor were three guest rooms, each with its own sitting porch and bathroom, as well as a large sewing room and quarters for the female servants. All the bathrooms were tiled and had separate bathtubs and showers.

In the hardwood-paneled basement was a pool room, billiards room, and bowling alley. The mansion was furnished in an Elizabethan style that included walls hung with tapestries. The estate had a separate underground heating and power plant, which also produced ice for part of the irrigation system and powered the mansion’s central vacuum system.

The grounds were as spectacular as the mansion. “For a background the house will have one of the most beautiful portions of the chain of hills back of the Beverly district,” reported the Los Angeles Times during construction of the estate. “The grounds slope upward to the base of these elevations and only at the rear will the grade be steep. Here the hill is being largely reclaimed by terraces and retaining walls of concrete, faced with brick. Flights of steps, capped with brick balustrades, unite the different levels, each of which will be laid out after a formal plan, with flower beds, trees and shrubs.” The architect also preserved an existing grove of native live oaks.

The grounds included a large conservatory, an aviary, stables, two summer houses designed to host garden parties, and a garage for seven cars, with quarters for male servants on the second story. The original swimming pool, in keeping with that era’s preferences, was covered by a glass roof, like a greenhouse.

The Thorkildsens moved into their hilltop castle in March 1913. But the Borax King wasn’t done yet. In September 1913, he bought the adjacent undeveloped eleven-acre property from Baroness Rosa von Zimmerman, which he had landscaped with rare, semitropical shrubbery, paved walkways, fountains, and pools. That boosted the estate’s size to twenty-five-plus acres.

Such a grand estate was only part of Thorkildsen’s remarkable life, which was envied by some people, and the subject of endless gossip by many more.

Before, during, and after construction of his hilltop castle, Thorkildsen devoted himself to a life of excess. He had one affair after another. He sometimes walked around parties at the mansion in the nude. He bought every new car that caught his eye. In 1915, he bought a 135-foot yacht, the Fiorgyn, which he sailed to the Panama Canal and to Hawaii. He went big-game hunting and filled his home with his trophies. He invested wildly in one business deal after another.

In November 1914, Dora formally separated from him. Their sensational divorce in October 1915 made headlines. Thorkildsen—daringly—had charged Dora with extreme cruelty, testifying that she verbally abused him in public and to his business associates, and that she had tried to kill him on several occasions.

He also claimed that it was Dora, not he, who had insisted on building the lavish Alpine Drive mansion and buying more and more property to expand the grounds. Dora didn’t dispute these claims. The court sided with Thorkildsen but, as he had made a property settlement on Dora in late 1914, the judge was forced to uphold that settlement.

Photo Credit: Author’s Collection.

Dora got the extraordinary Alpine Drive estate but could not afford to maintain the vast property. Nor could she find anyone willing to rent the estate for her asking price: $1,000 a month.

Finally, in February 1916, she was able to sell the estate for around $200,000 to John Joyce of Boston. A month later, she paid $14,000 for and moved into a ten-room Mission-style home on North Rodeo Drive across from the Beverly Hills Hotel.

The Alpine Drive estate’s third owner, John Joyce, was a Boston financier and vice president of the Gillette Safety Razor Company, which had been founded by one-time traveling salesman and amateur inventor King Gillette, and therein hangs a tale.

For centuries, men had taken their lives in their hands every time they shaved with a straight razor. Until King Gillette invented the disposable safety razor, which he started selling at twenty razors for one dollar in 1903. But Gillette lacked the capital to mass-produce his invention and make it truly successful.

Gillette approached John Joyce and asked for a major cash investment. Joyce tried the safety razor and knew a good thing when he saw it, so he gave Gillette the money . . . then stole the company away from its inventor, reaping the majority of its rapidly growing profits. Gillette had to settle for seeing his name become a household word, his mustachioed face on a hundred billion wrappers over the years, and a string of lawsuits against Joyce that left him with a minor share of the company’s enormous profits.

Both Gillette and Joyce moved to Beverly Hills in 1915. Gillette built his $50,000, twenty-room mansion on three acres on North Crescent Drive opposite the Beverly Hills Hotel. (The mansion later became the home of silent-movie star Gloria Swanson.) The much richer and more powerful Joyce purchased the Thorkildsen mansion and its twenty-six acres for $200,000 in 1916.

Joyce died a year later, but the Alpine Drive estate never went on the market. His daughter, Genevieve Joyce Johnson, inherited the estate, and she and her husband, Kirk B. Johnson, moved into the mansion, thereby becoming the property’s fourth owners.

Johnson had been a very successful banker in New York. He had then served as a captain in World War I. When the war ended, he retired from banking and moved to Los Angeles with Genevieve.

With unconscious irony, the Johnsons hired architect Elmer Grey (who had designed the site’s obliterated Nares residence ten years earlier) to make some upgrades to the mansion’s interior and the gardens. They also added an open-air swimming pool to the grounds, and erected a set of handsome red brick and limestone gates at the Alpine Drive entrance in 1919.

Still young, Johnson ended his early retirement to become president of the First National Bank of Beverly Hills. The couple had an active social life with all the “right people,” whom they entertained at their estate and met at the Los Angeles Country Club.

Then, in 1927, the Johnsons bought the Tajiguas Ranch near Gaviota and constructed La Toscana, one of Montecito’s greatest estates, designed by the skilled architect George Washington Smith. Landscape architect A. E. Hanson, who designed the gardens at La Toscana, recalled that they left Los Angeles and their twenty-six-acre Alpine Drive estate because they wanted “to get out of the hurly-burly of the city.”

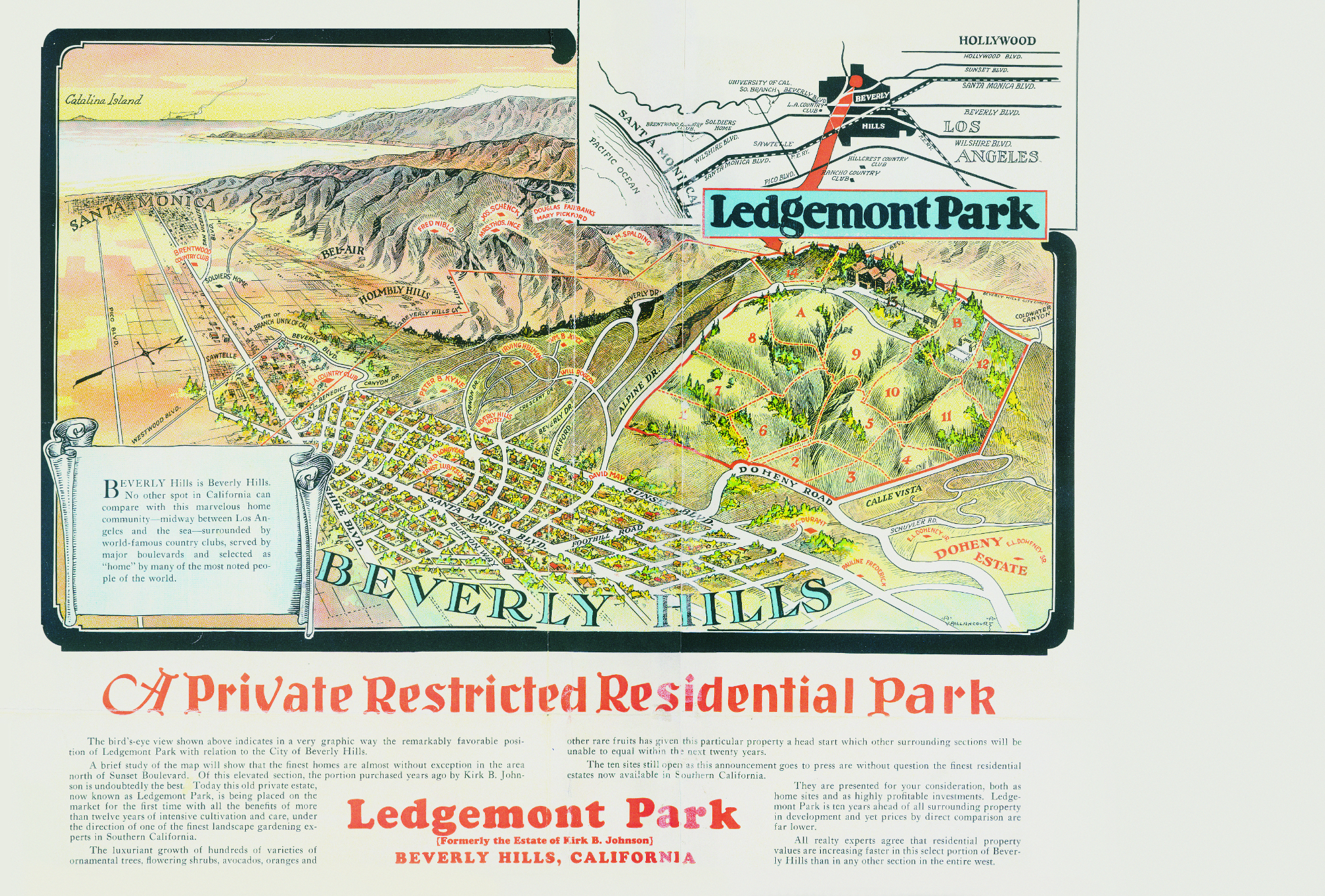

Before the Johnsons put their Alpine Drive estate onto the market, they decided to play the real estate game and make some money, like so many Angelenos in the booming late 1920s. They sold six acres to oil man Ralph B. Lloyd for his new estate (see page 348). In March 1927, they sold off another ten estate sites that would become the Ledgemont Park development where famed architects like Wallace Neff and Gordon Kaufmann designed some stylish mansions and gardens.

The years of John Joyce and Kirk B. Johnson—the third and fourth owners—had been quiet compared to the high jinks and extravagances of L. A. Nares and Thomas Thorkildsen, the first and second owners. With the departure of the Johnsons in 1927, the estate entered perhaps its most sensationalist years.

In July 1927, Margaret Keith became the Alpine Drive estate’s fifth owner when she paid $235,000—in cash—for the famed property. She made no changes to the mansion or the grounds. But she did bring new notoriety to the estate, and of a vastly different type than the freewheeling and free-loving L. A. Nares and Thomas Thorkildsen. Her story was one of great eccentricity, and pure tragedy.

Margaret Keith had grown up rich. She never married. Then, she was given $5 million by her father, David Keith, owner of several copper and silver mines, including the Silver King in Utah, the second largest silver mine in the world. Loving gardens and the ocean, she had quite reasonably settled in California. But Margaret Keith was not the most reasonable of people.

Since childhood, she had exhibited what her sister called “a family complex of loneliness,” from rocking compulsively in a rocking chair for hours on end, to locking herself in her room alone for days. She became a recluse when she was just nineteen.

In her Alpine Drive home, she communicated not with words but with handwritten notes. She fired any servant who looked at or spoke to her. She stripped most of the furnishings from her Beverly Hills mansion, and she covered all the windows with bed sheets. She slept in a hall, not a bedroom. She had a cat taste all of her food before she would eat it. In short, she exhibited the traits of a severe affliction, perhaps even paranoid schizophrenia. But because she was very, very rich, she was called eccentric, not crazy, by most people.

At the age of forty-nine, fearing she was going blind and would be denied forever “the flowers and the beautiful sea,” Margaret Keith chose instead to end her life. She wrote a series of notes that explained the reasons for her suicide and arranged everything, from how her body would be discovered to who would act as trustee of her estate. Surrounded by these notes, on April 28, 1933, she inhaled chloroform to kill herself.

Her funeral made headlines. “Every wish expressed by Miss Keith in notes found beside her body had been carried out to the letter,” reported the Los Angeles Times. “During the three days her body was held in state in a private room at Pierce Brothers mortuary a ten-piece orchestra played the dead woman’s favorite classical selections” in an adjacent chapel. Only a single woman attendant was allowed to view her body. “Fresh flowers were banked each day on her coffin and her burial robes were changed daily. . . . The simple funeral service was attended only by members of the wealthy spinster’s immediate family and a few servants. In conformance with her wishes, no eulogy was said over her body, no prayers were uttered and no religious ceremony was conducted.” Her body was cremated and her ashes scattered over the Pacific Ocean.

In her will, Keith left her estate, including the Alpine Drive mansion, to her favorite nephew, Albert C. Allen Jr., a rancher and writer who lived in Oregon. Her will was promptly contested by her sister, Etta Eskridge, to whom she had left $50 and the cancellation of a $4,000 loan; her half-brother, David Keith, to whom she bequeathed $10; and her niece, Mary Allen Towle, Albert’s sister. Their claim? That Margaret Keith was not mentally competent when she made her will on December 25, 1932.

When the dust finally settled following the testimony of hundreds of witnesses, Albert C. Allen Jr. still got the bulk of Keith’s estate. His sister, Mary Allen Towle, got $46,000. His four-year-old son, Albert C. Allen III, received a $50,000 trust fund. Sister Etta Eskridge and half-brother David Keith divided the remaining $145,900 of property between them.

Over the next five decades, several different families owned the Alpine Drive estate. Miraculously, the huge Elizabethan mansion remained standing, although many of its new owners sold off portions of its grounds until the property had shrunk to just two acres.

The mansion’s death knell came in the early 1980s as real estate values started spiraling upward in Beverly Hills and the cost of restoring an outdated mansion was more than an all-new home. A developer demolished the mansion for a new home. Today, only the brick gateposts remain from what had once been one of Beverly Hills’ most spectacular—and talked about—showplaces.

Legal Disclaimer:

EIN Presswire provides this news content "as is" without warranty of any kind. We do not accept any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images, videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright issues related to this article, kindly contact the author above.