The Right To Repair Movement Emerges

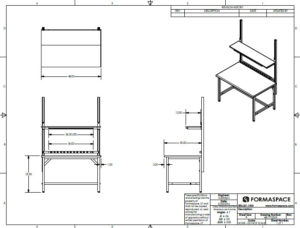

Formaspace builds custom industrial furniture for manufacturing and material handling at our factory headquarters in Austin, Texas.

The Right to Repair has become a flash point between manufacturers and consumers, arguing that independent mechanics can't make repairs to products they own.

What we now call the “razor and blades” business model was first popularized in the 1920s by the Gillette razor company. Consumers loved the cheap razors but loathed shelling out for the expensive blades.

The razor and blade model predates Gillette, who was inspired by Standard Oil’s practice during the late nineteenth century of selling heavily discounted oil lanterns – and expensive oil to fill them.

Other classic razor and blade examples include Kodak’s cheap and cheerful consumer cameras (that used expensive film and disposable flash bulbs) or the more recent introduction of cheap inkjet printers (which require pricy ink cartridges.)

Planned obsolesce is another business model strategy that got its foothold in the late 1920s as GM’s head of styling Harley Earl pioneered the annual fall model year change, designed to drive consumer demand by making existing vehicles look out of date.

Critics of planned obsolescence maintain it is inherently wasteful and adds unnecessary burdens on the environment.

Do You Own Your Product Anymore, Or Are You Just Renting It?

These days, offering “connected products” has become the business model of choice, but it too has a downside, as consumers realize they no longer “own” all of their purchases.

This practice started in the software industry, which thanks to the ubiquity of the internet, has shifted to a “software as a service” business model – forcing customers to essentially rent rather than own. The inflection point took place around 2010 – 2012 when Autodesk first made its industry-standard AutoCAD design software available via subscription, followed soon after by Adobe which moved its many creative software offerings (such as Photoshop) to the cloud.

As a business model, software subscriptions are genius. They reduce software piracy and eliminate the costly boom-bust cycle of having to convince users to purchase an upgrade to the latest version.

Yet it turns out the practice of “renting” access to software is not new; in the postwar dawn of IBM’s reign over corporate mainframe computers, IBM famously leased their systems (including tabulating cards), never allowing them to be sold outright or copied by other manufacturers – that is until the Justice Department stepped in to reach a 1956 consent decree limiting IBM’s monopolistic business practices.

Digitalization: The Drive To Make Every Device A Connected Service That Productizes Data

The advantages of the “software as a service” business model was not lost on the manufacturing industry – inspired by the likes of software platforms such as Facebook, whose “first mover advantage” helped it leverage Metcalf’s Law and the Network Effect to grow bigger and bigger.

These days, nearly every industry has sought to pursue this path of digitalization – hoping to turn their products into the next blockbuster connected device “platform.”

Industry advocates point to the early successes of this digitalization process, from the On-Star satellite service that can dial 911 after a vehicle crash to the ACARS system that alerts airlines and jet engine manufacturers of maintenance issues occurring in flight.

When questioned whether these practices infringed on consumers’ rights to repair or upgrade products they “own,” industry lobbying groups argued that tampering with embedded computer systems should be off-limits to consumers to assure system integrity and reliability.

In many cases, the government agreed with the industry’s point of view; for example, consumers cannot legally alter computer chips in vehicles that control safety features (such as airbags) or emission control devices.

Embedded Systems Allow Manufactures To Both Giveth And Taketh Away

However, there are examples where the manufacturers’ control over embedded computer systems appears to be motivated by the ability to prevent consumers from purchasing cheaper compatible third-party consumables and accessories or turning to independent repair shops instead of factory dealerships.

One of the most egregious examples has to be computer chips embedded inside disposable ink jet cartridges. Canon printers are notorious for this, and consumer advocates complain that these chips force customers to buy Canon ink at a cost of up to $12,000 per gallon.

(For schadenfreude fans, the recent pandemic chip shortage caused Canon to switch chip providers, causing some recent Canon printers to no longer recognize OEM Canon ink cartridges. Oh, the sweet irony.)

The Emergence Of The Right To Repair Movement

In the larger scheme of things, most consumers shrug off the high cost of things like OEM print cartridges as one of modern life’s inconveniences.

However, when John or Jane Doe take their vehicle to a trusted local car mechanic for maintenance – only to find out the mechanic can’t fix their car because the manufacturer has “locked them out” of the car’s computer system – consumers can get pretty angry.

Car mechanics first dodged the lockout bullet in the 1990s when the Federal government mandated car manufacturers add a standardized “OBD-II” diagnostic port to allow scanners easy access to data from the car’s computers, including the engine control unit (ECU) that monitors air pollution control sensors.

At the time, some manufacturers objected to “opening up” the data to third-party mechanics, hoping instead to keep the data proprietary (which would be a boon to their dealer’s service departments) – but the Feds shot this down.

However, by the early 2000s, car manufacturers began to computerize more and more functions while at the same time preventing individuals outside the dealer network from accessing repair documentation and crucial computer software diagnostic tools.

Independent car mechanics across the country began to organize, creating new lobbying groups to advocate for the legal “Right to Repair” products.

Read more...

Julia Solodovnikova

Formaspace

+1 800-251-1505

email us here

Visit us on social media:

Facebook

Twitter

LinkedIn

Legal Disclaimer:

EIN Presswire provides this news content "as is" without warranty of any kind. We do not accept any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images, videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright issues related to this article, kindly contact the author above.