Discretionary Adjustment or Pay Flexibility?

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Incorporating discretionary components within a company’s Annual Incentive Program has become increasingly common, particularly in the Real Estate and Financial sectors.

- Companies that have individual performance metrics in their Annual Incentive Programs tend to deliver higher payouts and executives are more likely to achieve target than companies that do not.

- Discretionary components in a compensation program generally shift pay more towards the Annual Incentive Program for companies in the Russell 3000, while having the opposite effect for the S&P 500.

- Individual performance metrics may be used as a substitute for discretionary bonuses for S&P 500 companies, but the opposite is true for Russell 3000 companies, where companies with discretionary metrics also award larger discretionary bonuses on average.

Metric selection in an Annual Incentive Program (AIP) gives company directors the opportunity to tailor compensation plans to the specific circumstances of the company’s named executive officers (NEOs). Often this decision revolves around competing goals as the compensation plan is expected to compensate NEOs for the opportunity cost of their time, reward exceptional performance, retain talented individuals, and incentivize high effort and productivity. While a well-designed Annual Incentive Plan considers all of these factors, shareholders generally prefer AIPs that display a clear relationship between shareholder value creation and executive pay.

Traditionally, metric selection for an AIP has focused on preset, quantifiable metrics so that clear goals can be established at the beginning of a performance period. However, firms have also included individual performance metrics (IPMs) that reflect non-financial objectives such as individual performance, strategic and personal goals, and other more qualitative and subjective measures.

These qualitative metrics allow compensation committees a greater degree of flexibility in rewarding executives. While preset, quantitative metrics may be assessed more easily by shareholders, a weak metric may lead to opportunistic behavior on the part of executives in pursuit of a singular goal at the expense of shareholder value. Complementing traditional metrics with IPMs may mitigate the noise of other performance measures by allowing directors to reward executives more holistically.

A more cynical view is that these IPMs are used as a substitute for discretionary adjustments and to ratchet up pay. A compensation committee always has the discretion to alter payouts, but expost adjustments usually generate significant shareholder pushback. This is especially true if an executive performs below his or her target within several financial metrics, and the compensation committee uses its discretion to restore final payouts back to near-target level.

Having some percentage of executive compensation tied to factors that are difficult to adjudicate may be a way for compensation committees to retain the power of discretion without losing the support of shareholders.

This paper focuses on how IPMs allow compensation committees to set discretionary performance targets. The analysis looks at IPMs within Annual Incentive Programs across 2,124 companies in the S&P 500 and Russell 3000 to determine how often they are used and what their impact is on executive pay. Given the lack of transparent disclosure for many instances of these metrics, it was nearly impossible to evaluate goals and payouts at a metric level. Instead, this paper divides companies into those that do and do not use IPMs and compares compensation patterns within the two groups. The goal of this analysis is to determine whether there are any noticeable differences among companies that utilize IPMs, and whether IPMs led to higher incentive program payouts. It should be noted that the analysis here implies correlation rather than causation.

Gaining Momentum

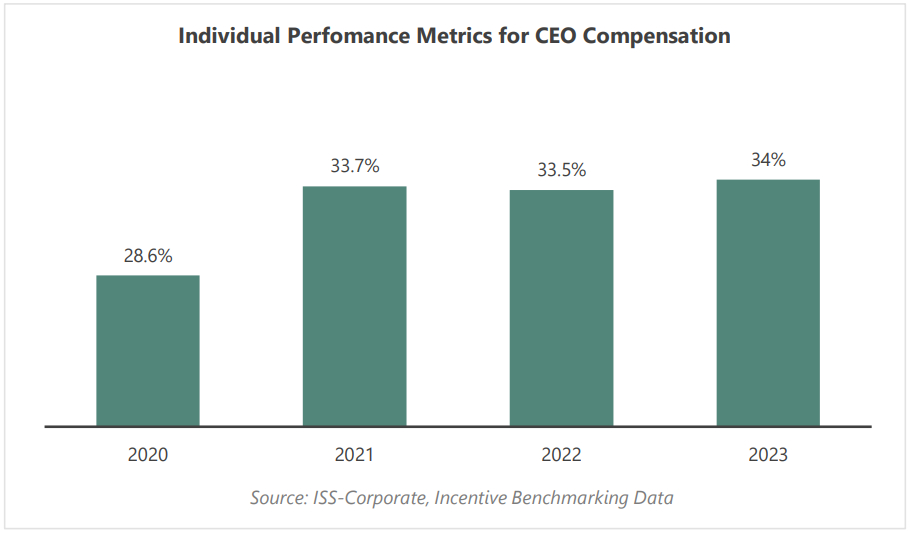

IPMs were utilized by approximately 34% of companies across the S&P 500 and Russell 3000 during FY 2023 compared with 28.6% in FY 2020.

IPMs noticeably spiked during FY 2021, probably as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Many companies may have sought increased flexibility within their AIP design following a unique 2020. Incorporating discretionary metrics such as IPMs allowed for increased flexibility during FY 2021 and beyond to cope with greater levels of uncertainty regarding AIP payouts. Over the last three years, the use of IPMs has remained stagnant, and they do not appear to be reverting to FY 2020 levels. With individual performance metrics becoming more common than they were just three years before, we also found it important to investigate which industries use these metrics more prominently

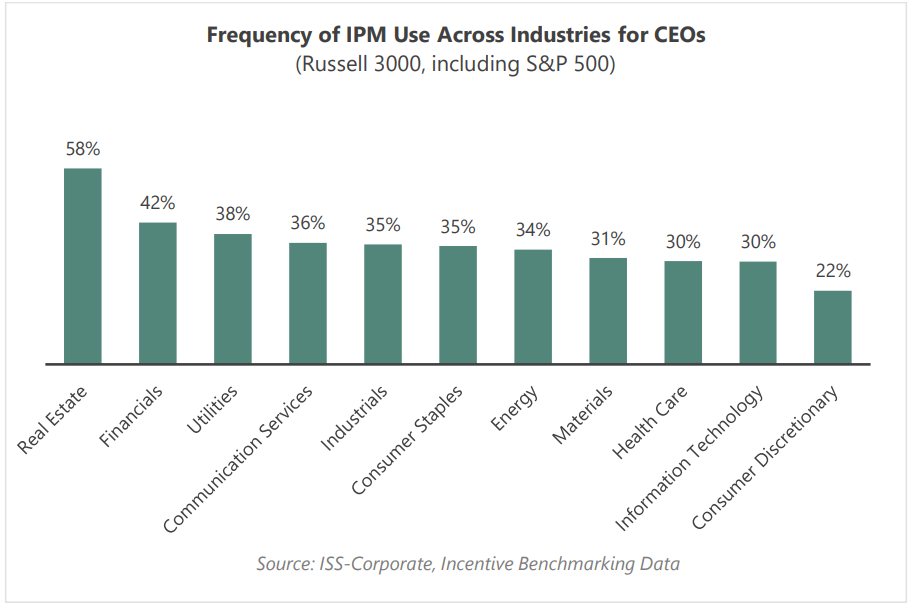

In FY 2023, Real Estate used the most individual performance metrics by a wide margin, while the Consumer Discretionary sector used them the least. These differences may tell us which industries tolerate committee discretion more. Potentially, it may be more difficult for Real Estate to pinpoint preset metrics that reflect the performance of executives, while the Consumer Discretionary sector has several preset metrics that measure overall CEO performance well.

Higher and Higher

Observing whether companies with IPMs are more or less likely to achieve “target” payout, defined as 100% of the base salary, may help us evaluate the two theories surrounding individual performance metrics. If companies use individual performance metrics for the sole purpose of flexibility, then payout may vary for one company in comparison to companies with entirely preset metrics, but average compensation across indices should be unaffected by the inclusion of the discretionary metric.

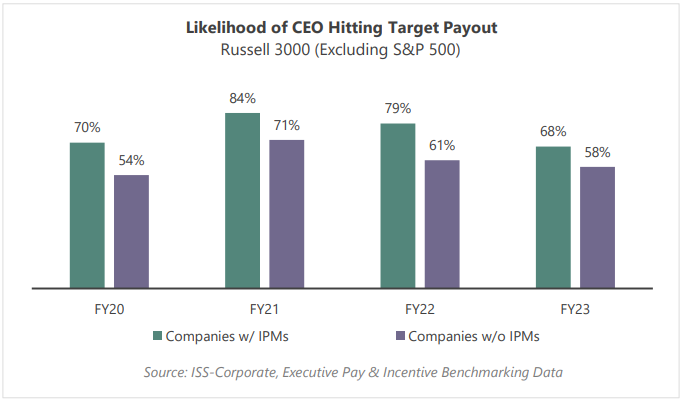

Our findings suggest that across both the S&P 500 and Russell 3000, companies that use IPMs were more likely to achieve target level outcomes within their AIPs. Among the Russell 3000 companies in FY 2023, 68% of companies that utilized IPMs achieved at least a target level of performance for their CEO’s AIP compared with 58% of companies lacking IPMs.

We also reviewed the three prior fiscal years to ensure that this was not a one-year trend. As displayed below, companies that incorporate IPMs in their AIP have consistently achieved target level performance for their CEOs more often than companies that do not use IPMs.

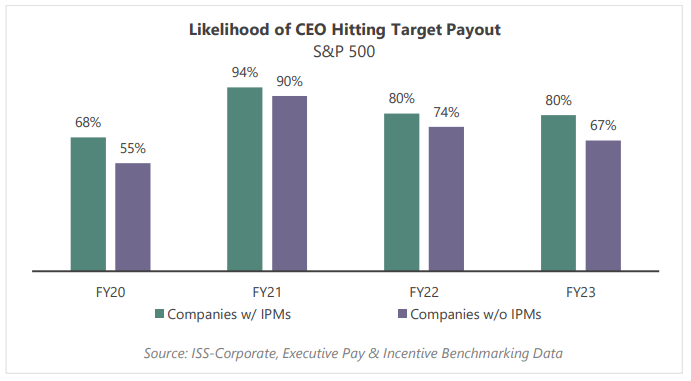

The trend remained consistent when analyzing only S&P 500 companies. During FY 2023, 80% of the S&P 500 companies reviewed saw their CEO achieve a target level of performance in their AIP when the program had IPMs. This is 13% higher than the 67% of CEOs that achieved target performance that did not have IPMs.

Looking at past years, the difference in target outcomes was less pronounced than in 2023. This was especially true during fiscal 2021, when 94% of CEOs with IPMs hit target compared with 90% at companies that did not have IPMs. However, in every year since 2020 among S&P 500 company CEOs, AIPs with IPMs achieved target performance more often than programs that did not use these metrics.

Any company can craft their compensation discussion & analysis disclosure to justify the usage of an individual performance metric and how crucial it is to account for executive performance. The argument for having an individual performance metric is that there needs to be some judgement of executive performance outside of the financial metrics that are meant to link shareholder interests and executive pay. Not all companies would be willing to raise payout to target after financial metrics performed below expectations. However, based on the data across the Russell 3000 and S&P 500, there is a possibility that companies do not hesitate to use IPMs to increase AIP payouts. That may raise questions over whether the additional flexibility is justified or whether it’s a vehicle to increase discretionary pay for executives. Perspectives may vary, but it is nonetheless noteworthy that AIPs with IPMs consistently have a greater chance at a target level payout.

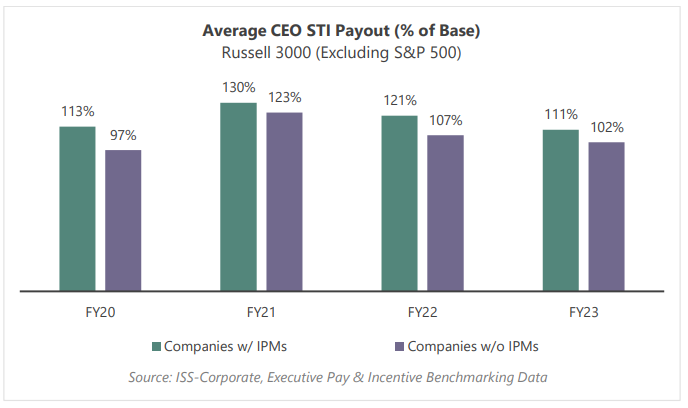

We reviewed average overall payout levels for AIPs when they incorporated IPMs. Among Russell 3000 companies, the average final AIP payout to CEOs was 111% of base salary for FY 2023 for companies that used IPMs. For companies without an IPM for their CEO, the average payout was 102%.

Consistently over the last four years the average AIP payout was higher among companies that utilized IPMs across the Russell 3000. This solidifies that Russell 3000 companies that incorporate IPMs are more likely to pay their CEO a greater Annual Incentive Program payout than companies that do not have these metrics present.

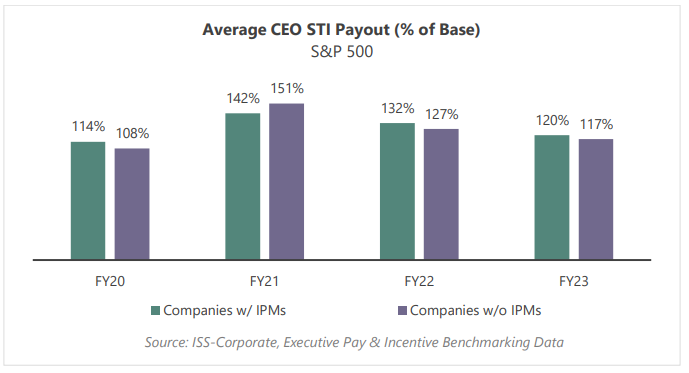

The results were similar in the S&P 500 with the exception of FY 2021, though the difference in payouts was less pronounced. This may suggest that S&P 500 companies are more conservative in terms of assigning higher payouts when incorporating discretion in their Annual Incentive Program. S&P 500 companies are larger and more closely scrutinized in the media than the rest of the Russell 3000, so they may be more reluctant to grant CEO payouts that are not closely aligned with the achievement of financial targets.

Companies that use IPMs tend to pay their CEOs more than companies that do not use IPMs based on the short-term incentive (STI) payout data. Questions may surface from this result, such as whether the higher pay is warranted and/or whether companies are using these metrics to increase payouts that may not be justified.

An anomaly in these S&P 500 payout data is that during FY 2021, payouts were higher to CEOs that did not have IPMs within their Annual Incentive metrics. One reason for this difference was that the year immediately followed the pandemic’s appearance in FY 2020, where compensation was extremely high across the board. As seen in the chart above, nearly 90% of companies achieved target payout. FY 2021 may indicate a reaction to the pandemic and the subdued performance during FY 2020. A similar trend is seen with Russell 3000 payout data above where the impact of IPMs and payouts were not as pronounced during fiscal 2021.

The Short End of It

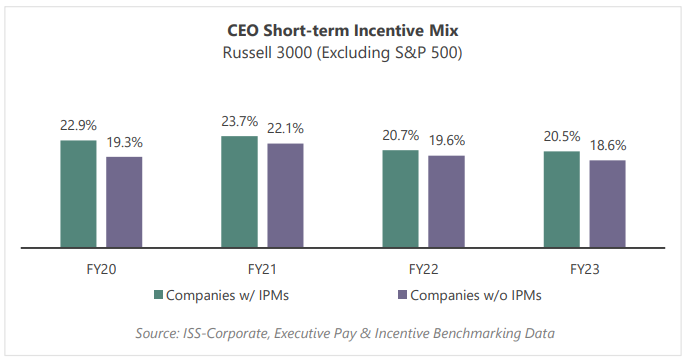

After looking at the impact of individual performance metrics on overall compensation levels, we tried to observe their effect on the composition of short-term versus long-term pay. Our first finding was that companies across the Russell 3000 with IPMs have a greater percentage of total CEO pay-mix attributed to Annual Incentive Programs as opposed to those that do not utilize IPMs.

Over the last four years, this trend has stayed consistent in that Russell 3000 companies with individual performance metrics in their AIP pay their CEOs a greater percentage of short-term incentive pay than companies that do not use these metrics.

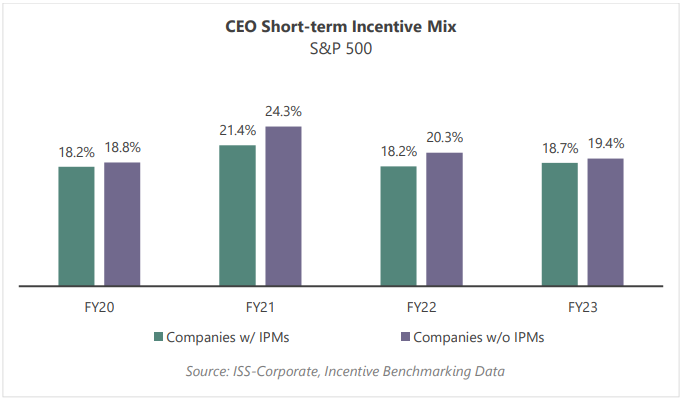

However, we found that this same trend doesn’t apply to S&P 500 companies. Since FY 2020, S&P 500 companies with IPMs in their AIP based a smaller portion of their CEO pay-mix on AIP payouts. This may mean that S&P 500 companies are more judicious than the Russell 3000 in terms of using discretionary metrics. S&P 500 companies are usually held to a higher standard than Russell 3000 companies. This could also reflect larger equity payouts for companies with IPMs because of the smaller makeup of short-term pay.

Discretionary Metrics or Discretionary Bonus?

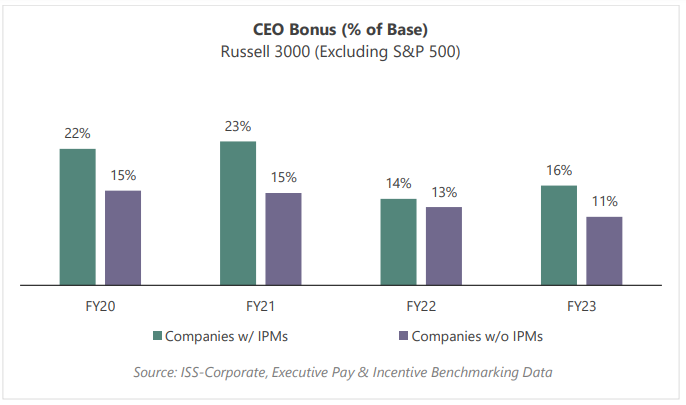

Are these discretionary metrics used as a substitute for a standard discretionary bonus? The answer may depend on the size of the company. The graphs below show the average bonus in the Summary Compensation Table for companies with and without individual performance metrics. Russell 3000 companies with discretionary metrics have larger bonuses than those without. This suggests that the metrics are not used as a pure substitute. Combined with the analysis above, it seems that Russell 3000 companies have increased short-term pay that includes both discretionary metrics in AIP’s and separate discretionary bonuses.

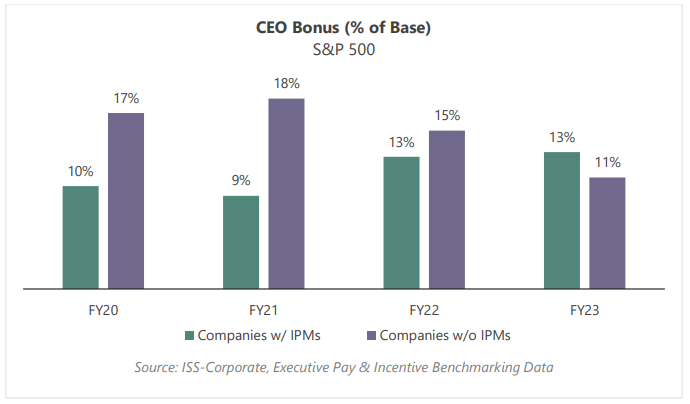

Companies in the S&P 500 show the opposite. Companies with IPMs generally have lower bonuses. This suggests that companies could be using these metrics in place of bonuses, which are generally subject to greater scrutiny. Given the higher standard associated with S&P 500, we find this theory plausible.

Conclusion

Our analysis suggests differing purposes behind individual performance metrics depending on size and industry. Russell 3000 companies, for example, typically have higher short-term pay and larger bonuses accompanying the individual performance metrics, while S&P 500 companies tend to use the individual performance metrics as a replacement for bonuses. Furthermore, IPMs are significantly more common in certain industries. This diversity of implementation reflects competing objectives compensation committees face when selecting a metric to evaluate CEO performance.

The results also suggest that investors should carefully evaluate programs that lack pre-set quantifiable metrics. While IPMs add needed flexibility to a CEO’s pay package, they can also subtly lead to an increase in short-term pay. Companies with IPMs are more likely to hit their target payout, and short-term payouts may be significantly higher as well. In short, the results suggest an important role for monitoring AIPs with a heavily weighted individual performance metric and it is incumbent on companies to provide adequate disclosure.