Timber Management Can Help Wildlife in the George Washington and Thomas Jefferson National Forest

Logging mature timber is a must to restore new growth to the forest floor. Poor timber management is a formula for declining wildlife habitat.

By Tee Clarkson for Whitetail Times

Photos by Department of Wildlife Resources

When it comes to hunting and recreational opportunities on public lands, Virginians should consider themselves fortunate. Counting state-owned lands that allow hunting, military bases, and national forests, hunters in Virginia have somewhere in the neighborhood of 2,500,000 acres at their disposal. Safe to say, it would take multiple lifetimes and more pairs of boots than one could count to cover all of the nearly 3,900 square miles of public property open to hunting in Virginia.

By far the biggest section of public property allowing access to hunters are the George Washington and Jefferson National Forests (GWJNF), which together make up nearly 1.65 million acres in Virginia, roughly two-thirds of Virginia’s public lands open to hunting.

This is the sort of massive swath of land that can allow a hunter to get off the beaten path and pursue his or her quarry in a different manner than how many hunt in the eastern part of the state where human populations are high and large tracts of public land few.

While one might think a large expanse of public access would send hunters headed towards the mountains, the trend is moving in the opposite direction. Hunter license numbers are falling across the state (350,000 big game licenses were purchased in 1988. Only 225,000 were purchased in 2012 according to the most recent Deer Management Plan released by the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources in 2015). Last year it was closer to 200,000. Additionally, hunter numbers have declined significantly in the National Forests over the years. In 1992, hunters purchased 107,975 National Forest Hunting permits. By the 2018-2019 season, that number had fallen to 57,436 permits, a 47% decline.

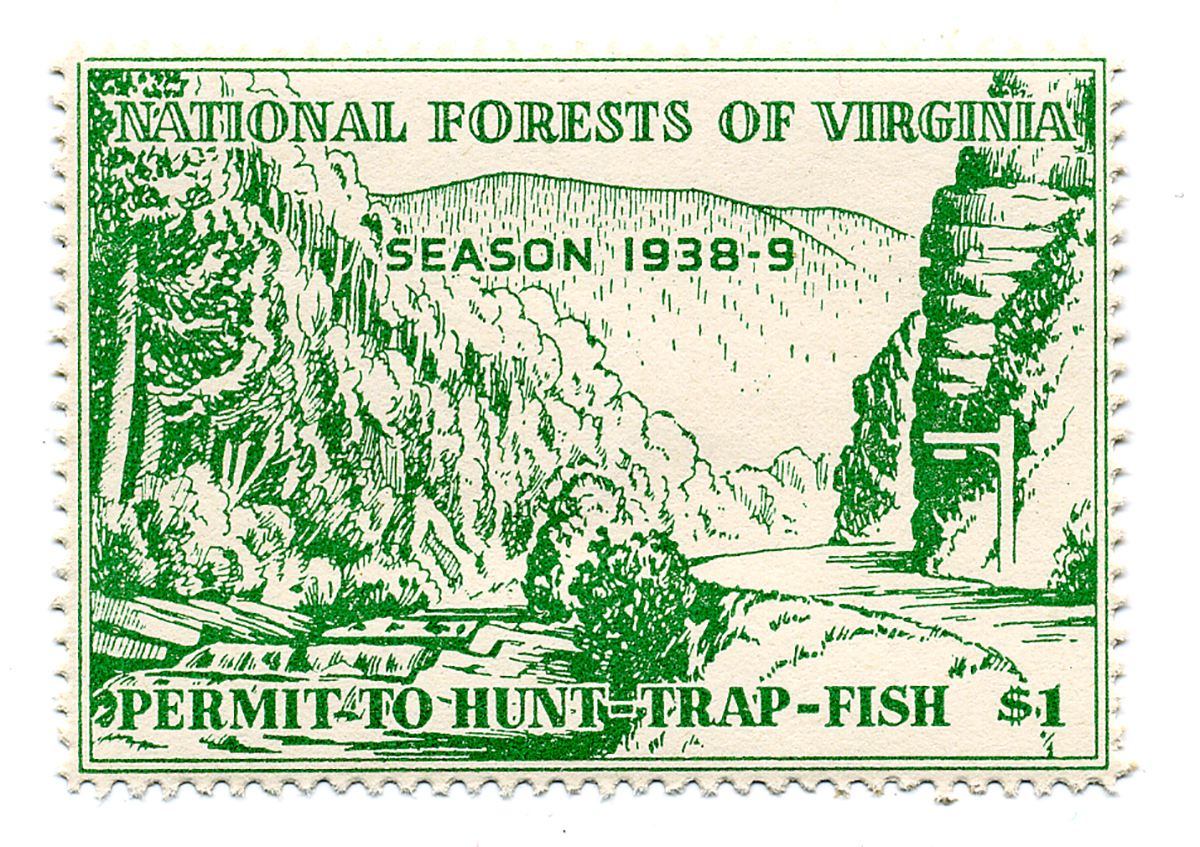

Virginia first introduced the National Forest Stamp for the 1938-39 season. The $1 permit to hunt, trap and fish is a long-standing history of public use on the George Washington and Thomas Jefferson National Forest in the Old Dominion.

It’s safe to say that declining wildlife numbers, namely game species like, deer, turkey, and grouse, are a significant contributing factor keeping hunters from the woods of the GWJNF.

Since the mid 1990s the deer harvest on public land west of the Blue Ridge has fallen by a whopping 64% according to DWR’s Deer Management Plan.

Similarly, between 1996 and 2012, wild turkey populations in the George Washington National Forest declined by nearly 50% according to the Wild Turkey Management Plan.

So, what happened?

The answer isn’t exactly simple. Certainly the reduced numbers of hunters has led to lower deer harvest, but the harvest has fallen by more than twice the decline in hunters throughout the state. Clearly other factors are at play.

At the top of that list is declining wildlife habitat in the GWJNF, and at the center of that issue lies the lack of timber harvests that produce early successional habitat like clear cuts and shelterwood cuts (cuts that leave relatively few trees). Of the 1.8 million acres that make up the GWJNF, the vast majority is trees, 87% of which are more than 70 years old. This isn’t a natural state of forest, and certainly isn’t a place where animals, birds, and important pollinator species can survive, much less thrive as they once did.

The Forest Service provides a significant history of the Appalachia region on their website, painting a picture of a landscape in southwestern Virginia that was vastly different than what exists today:

“Prior to European settlement, the landscape of southwestern Virginia included forests of different ages interspersed with expansive open woodlands with grassy understories, and occasional dense cane thickets, barren areas, and swamps. Forests were constantly changing as a result of receding of the glaciers to the north, fantastic beaver activity, large grazing animals like the eastern woodland bison, uncontrolled lightning fires, and widespread Native American use of fire and crop cultivation.”

As European settlers expanded westward in the 1800s, the picture of the landscape began to change, and change rapidly. Logging of the southwestern part of Virginia and the entire Appalachian region began in earnest in the 1800s and peaked in the early 1900s. What was once a landscape rich in species diversity was now a barren wasteland of cutover and slash where wildfires raged and floods muddied the once clear and clean waters.

The result didn’t go unnoticed. Efforts to protect the forest, with support of large timber companies, started in the late 1800s. The federal government began purchasing large tracts of land in the Virginia mountains. Gradually many of the tracts were combined over the years. In 1917 the Shenandoah National Forest was created (later renamed to the George Washington National Forest). The Jefferson National Forest would follow in 1936. The two were combined administratively in 1995.

With the formation of national forests like the GWJNF and others throughout the southeast, the trees began to grow back and wildlife populations rebounded. In reaction to the large-scale fires which had ravaged the country in the previous century, the use of fire for land management was discouraged and the Forest Service stationed fire wardens throughout the region to put out fires as soon as they started.

Those trees that began growing in the early to mid-1900s are the ones that now make up the 87% of the GWJNF’s trees that are over 70 years old.

It’s not that these older trees aren’t important for the wildlife populations. They are. What is lacking are the younger stands of trees (early successional habitat) that offer a variety of soft mast that is important to a number of species. However, perhaps one of the most important benefits is that the high stem density in younger stands offer protection for animals in general and when breeding and rearing young. This density helps animals hide and avoid avian predators (owls and hawks kill a lot of grouse for example).

Currently less than 1% of the GWJNF is made up of stands between 0-20 years old. This lack of varied and younger habitat has undoubtedly had a negative effect on game and non-game species throughout the area.

Deer hunting on the national forest has drastically declined in recent years. The lack of timber harvest has resulted in the loss of critical forest diversity and wildlife habitat that greatly affect the whitetail population.

What is being done?

The Revised Land and Resource Management Plan for the George Washington National Forest that was released in 2014 by the Forest Service calls for early successional habitat from 4% to 13% in forested areas, depending on tree species.

Getting to and maintaining these numbers will require both timber harvest and the use of prescribed fire on landscape scale projects, and will include much public comment.

The George Washington National Forest Stakeholder Collaborative effort started in 2010 to offer input on the Revised Land and Resource Management Plan for the GWNF. The George Washington Stakeholder Convener’s Group, a partnership facilitated by TNC, continues today to help implement the GW Forest Plan. The Convener’s Group efforts include attention to wildlife, water, restoration, communities, wild places, recreation, and forest products. Hunting organizations are well represented and work together with a variety of forest users to maintain a mosaic of undeveloped and actively managed forest conditions.

Once a clear cut or timber thinning has been completed, the increased sunlight to the forest floor will start to germinate new growth. The much-needed wildlife habitat that the National Forest so desperately needs.

The Lower Cowpasture Restoration and Management Project has served as shining example of what partnership, planning and good science can do in managing the forests and waters within the GWJNF. The project, which began in 2017, includes restoration activities on both public and private lands spanning some 117,500 acres. Partners in the project include the U.S. Forest Service, Trout Unlimited, the Virginia Department of Forestry, the Nature Conservancy, the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, the Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation, Mountain Soil and Water Conservation District, VA Wilderness Committee, National Wild Turkey Federation, Virginia Bear Hunters Association, Virginia Deer Hunters Association, American Chestnut Foundation, Cowpasture River Preservation Association, VA Forestry Association, Dabney Lancaster Community College, Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, Virginia Department of Transportation and the Virginia Wildlife Habitat Coalition.

The goal of the project has been multifaceted: to restore the health, diversity and resiliency of fire adapted forests and rare plant communities, to improve habitat for forest bats and declining early successional birds, to improve water quality, function, and connectivity of streams, and to remove invasive plant species while restoring native plant diversity and pollinator habitat.

All of these actions will be good for the primary game species within the GWJNF like deer, turkey, bear, and grouse.

By in large, the project is becoming a tremendous success, but it has not been without its struggles. Low timber prices have made harvest difficult in some areas, according to Elizabeth McNichols, District Ranger for the James River and Warm Springs Districts of the George Washington and Jefferson National Forests.

Decreased staffing in the Forest Service hasn’t helped either. Add in public comment periods required by the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), and other tedious bureaucratic procedures and large scale restoration projects can get bogged down.

McNichols notes “the biggest success is the collaborative way the process has been put together.” She added that the Forest Service has sold more volume of timber in 2019 than in a long time.

“We need to keep our sights on the GWJNF Forest Plans, which call for an annual 3,300 to 6,400 acres of regenerating young forest timber harvests. These harvests are essential for restoring the forest to a natural diversity essential to overall forest health and resiliency,” said Wayne Thacker, Chairman of the Virginia Wildlife Habitat Coalition. “Timber harvests have been averaging about 700 acres a year for the last decade. At this rate we lose at least 2,600 acres of critical forest diversity and wildlife habitat each year.”

The Nature Conservancy (TNC) is playing a significant role in the Lower Cowpasture Project and implementing the forest plan.

“The Nature Conservancy’s focus is on biodiversity conservation, and we believe that a variety of different habitats occurring together, from young forest to old-growth, is what will keep the Appalachians healthy and diverse,” said Blair Smyth, Director of the Allegheny Highlands for TNC.

“The George Washington Forest plan gives the U.S. Forest Service a path forward to work towards that more diverse forest. The Nature Conservancy and other partners are working to help implement that plan because it recognizes the value of all habitat—from old-growth to young forest. Wilderness designations create large areas of undisturbed forest, while management designations allow for the use of needed management activities like prescribed fire and timber harvesting,” Smyth noted.

So far, there have been more than 1,900 acres of timber harvested in the Lower Cowpasture Project area. This includes clear cuts, shelterwood cuts, and pre-commercial thinning.

“To make changes at the landscape level, you have to do these big projects,” Smyth said.

Thacker thinks mistaken public opinion focused against timber harvest has influenced a reduction of active timber management in GWJNF. He noted that Virginia’s hunting organizations recognize the importance of providing public input to support restoring forest health and resiliency through active forest management and encourages organizations to keep its members informed of GWJNF management needs.

Returning to the glory days of wildlife populations west of the Blue Ridge may be unlikely in the near term, but landscape scale projects like the one in the Lower Cowpasture River provide hope that through partnerships and education, through timber harvest and the use of prescribed fire, wildlife populations will begin to rebound.

“We’ve got to get involved,” Thacker said. “Individuals are important.”

Editor’s note: Tee Clarkson has been writing about Virginia’s wildlife for the past 17 years. He is a regular contributor to The Virginia Sportsman, Virginia Wildlife and wrote the Outdoor Column for the Richmond Times Dispatch for five years. Currently he runs an outdoor business for kids, Virginia Outdoors and works in land conservation throughout the Commonwealth with Atoka Conservation Exchange. Readers can reach out to Clarkson via email at tsclarkson@virginiaoutside.com with questions and comments.

©Virginia Deer Hunters Association. For attribution information and reprint rights, contact Denny Quaiff, Executive Director, VDHA.

Hunting During the COVID-19 Outbreak

- If you choose to hunt during the pandemic it is essential that you follow CDC guidelines.

- Purchase your hunting license online instead of in-person.

- Hunt alone or with family members or others that you live with and are isolating with during the Governor’s “stay at home” order.

- Do not hunt if you feel sick or think you might be sick.

- Stay at home when you are sick, except to get medical care.

- Wash your hands regularly with soap and water for 20 seconds or using alcohol-based sanitizer even while afield or afloat.

- Do not share equipment with anyone, and wash your equipment when you’re done.

- Stay at least 6 feet away from other hunters you encounter and try to avoid crowded access points.

- Try to hunt near home as much as possible and avoid traveling long distances.